Following are some of the fascinating papers which will be presented this coming Saturday May 7th at The Annual Research Symposium of the Fashion and Textiles: History, Theory, Museum Practice Program at FIT’s School of Graduate Studies.

CONSTRUCTING A SOVIET NARRATIVE: JEAN PAUL GAULTIER’S RUSSIAN CONSTRUCTIVIST COLLECTION, 1986

By Doris Domoszlai-Lantner

Thierry Mugler Les Milteuses’ Communist-style dress, Autumn/Winter 1986-87. Image source: http://thierrymugler.tumblr.com

As the Soviet Union drew its last breaths, major design houses created collections that included garments and accessories, which drew upon its impending collapse. The year 1986 was particularly significant, as the Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s complementary policies, glasnost and perestroika, found their place on some of fashion’s greatest runways. Although houses such as Thierry Mugler and Yves Saint Laurent sent Soviet-inspired pieces marching down their Fall/Winter 1986 runways, the fashion world’s enfant terrible, Jean Paul Gaultier’s, collection was arguably the most expressive. Gaultier brushed past the overt Soviet militarism that his colleagues had drawn upon, and instead, focused on the early period in the union’s history during which the Russian Constructivist art movement formed and thrived.

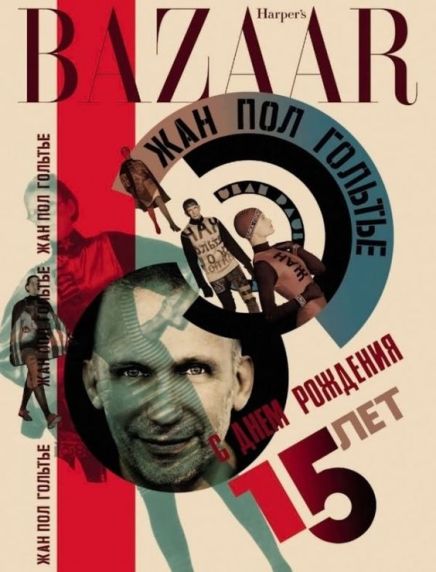

1986-87 Jean Paul Gaultier russian collection on Harpers Bazaar cover

With a stage and runway set to underscore the terminology and and philosophy of the Constructivists, Gaultier presented his collection as an homage to, and dialogue with, some of the Soviet Union’s most devoted, politically-charged, and prolific artists. In his collection, Gaultier utilized many of the techniques and motifs from the Constructivists’ body of work. He captured the essence of the Russian Constructivist aesthetic by integrating Cyrillic letters and numbers in block type, linear and geometric forms, and photomontage, in a color scheme that was analogous to, and nearly duplicated that of his Soviet comrades.’ Gaultier delved into the precarious social and political climate of the Soviet Union, drawing numerous connections between his own work and that of the Constructivists, and the USSR’s policies at the time.

Reverberations of this collection continue to be felt nearly three decades after its debut: it was featured on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar Russia’s fifteenth anniversary issue, and is the basis for numerous contemporary designers’ collections. Undoubtedly monumental, Gaultier’s Russian Constructivist collection has a longstanding legacy that underscores its importance in fashion and Soviet history.

ECONOMIC CRISIS AND THE BLOOMINGDALE’S EXPERIENCE, 1973-1975

By Rebecca Love

In the 1970s, Bloomingdale’s commissioned artists to create shopping bags for the store. http://www.thedepartmentstoremuseum.org/

In his 1975 state of the Union address, President Gerald Ford was not optimistic. He said, “I must say to you that the state of the Union is not good.” As Ford went on to detail what was not working, it became clear that the root of the current crisis was the economy. He continued, “Prices are too high and sales are too slow … I’ve got bad news and I don’t expect much, if any, applause.” Starting in 1973, the United States had been struggling to maintain the fiscal strength and stability it had enjoyed since the end of World War II. A gas shortage, high unemployment, and massive national debt as a result of the Vietnam War were all parts of the economic downturn. In December of that same year, however, Time Magazine ran a cover story about the “U.S. Shopping Surge”, pointing towards “trendy Bloomingdale’s” as the center of this retail activity. At a time when it seemed like America and its people were running out of money, Bloomingdale’s was enjoying higher sales and peak popularity.

A large part of the success of Bloomingdale’s during this time was its creation of a shopping playland. Products and promotions centered around a setting that did not reflect the failing economy. Fashion had begun to turn away from the fussy precision and prohibitive expense of couture and Bloomingdale’s used this to its advantage. Bloomingdales launched its own boutique layout, embracing emerging designers as opposed to established couture labels. These designers were often given their own in-store boutique where shoppers could immerse themselves in the artist’s aesthetic without the obligation to buy. Similarly, Bloomingdale’s expanded its cosmetics department, encouraging visitors to spend time at the counters to receive advice and makeovers. A longtime pillar of Bloomingdale’s success, the home furnishings department was celebrated in a 1973 home decorating book that featured such fantastical decor as cardboard furniture and a room designed to look like a cave. For New Yorkers living in a city where the economic collapse was especially destabilizing, Bloomingdale’s had become a place of fantasy. In 1973, Lori Gould wrote in the March 15th issue of New York Magazine, “What it all signifies, I think, is that Bloomingdale’s, at the ripe age of 100, may be the only store in the world that doesn’t act like a grown-up.”

This paper examines the financial and popular success of Bloomingdale’s between 1973 and 1975, a period during which the American economy was at its lowest point since before the second World War. Bloomingdale’s strength in the fashion sector is compared to the drop in sales suffered by other stores such as Lord & Taylor, Bergdorf Goodman, and Neiman Marcus. In the midst of high unemployment, union strikes, soaring inflation, an oil crisis, and what is described by economists as a national “malaise”, Bloomingdale’s sold fantasy in the form of a fashionable lifestyle, a model which proved especially effective for the store throughout the 1970s.

I GAVE GOLD FOR IRON: THEMES OF PATRIOTISM IN BERLIN IRONWORK JEWELRY

By Naomi Sosnovsky

Bracelet Place of creation: Germany Date: 1830s Material: cast iron Inventory Number: ЭРРз-809, Hermitage Museum

“Gold to the Fatherland! I gave gold for defense; I took iron as an honor.” Born out of and nurtured by the crisis of war, the Prussian cast iron industry produced adornment that embodied the nation’s strong fighting nature and stirred deeply patriotic emotions among its people. German commemorative propaganda posters circulating during the Great War embodied the same nationalistic spirit saturating the country exactly one hundred years prior during Napoleon’s occupation. Originating in Prussia in 1806 and enduring through the 1871 unification of Germany, Berlin ironwork jewelry rooted itself in the country’s economy, architecture, and fashion.

Following an appeal by Princess Marianne of Hesse-Homburg in 1813, gold jewelry was given in trade for a cast iron surrogate as a means of raising funds for an uprising against Napoleon. The fashionably designed iron jewelry became widely popular most notably because it allowed for an understated demonstration of national pride.

This paper will explore a one-hundred year period of wartime fundraising and fashion using extant examples of jewelry, propaganda, and illustration in a study of romantic nationalism and German memory culture. In an exploration of the gendering of patriotism, iron jewelry will be investigated as an opportunity for female wartime contribution and a device for the public display of solidarity.

Samuel Neuberg

DRESSING FOR THE REVOLUTION: AN ANALYSIS OF FASHION AND DRESS IN THE MEMOIRS OF MADAME DE LA TOUR DU PIN

Henrietta-Lucy Dillon, the Marquess de La Tour du Pin’

A pivotal moment in the foundation of modern European history, the French Revolution began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. Not only a revolution of politics and ideas the Revolution was one of fashion as well. As Balzac observed the Revolution was “a debate between silk and broadcloth.” Influenced by progressive Enlightenment ideals, the Revolution saw the inversion of French social hierarchy as French citizens uprooted the centuries-old socio-political systems of the Ancien Regime; rejecting the systematic oppression which stratified French society into rigidly stratified social hierarchies recognizably categorized by strict sumptuary laws. Aristocratic decadence was abhorred and the silk and satin fineries of the Ancien Regime were abolished in favor of universally plain and simple cloths of the people.

Written between 1820 and 1853, The Memoirs of Madame de La Tour du Pin provide a first person account of the radical changes brought on by the French Revolution. Born into the aristocracy of the Ancien Regime Henrietta-Lucy Dillon, the Marquess de La Tour du Pin’s memoirs cover her life at the court of Louis XVI, the crisis brought on by the Revolution, her life in exile as a political refugee, the trials of returning to France under the Directoire government, and her life during the first year of the Restoration. A witness to a rare moment in history Dillon’s memoirs are rich in their detailed descriptions of clothing and dress, tracking both the subtle and swift changes to fashion and dress brought on by the Revolution. Though much has been written broadly about fashion in France before, during and after the Revolution, Dillon’s memoirs offer fashion historians a unique opportunity to assess how the crisis of the French Revolution affected fashion and dress on an individual level.

For this paper I will engage in a critical analysis of Dillon’s memoir from the perspective of a fashion and dress historian, assessing the role that clothing and dressed played in mediating her transition from Ancien Regime aristocrat to political refugee of the French Revolution. I will supplement Dillon’s written accounts of clothing and dress with contemporaneous works of visual culture in an attempt to illustrate Dillon’s memoir and place it within the broader context of the political fashion revolution which rocked France in late eighteenth century.