By Landis Lee

Today, in the twenty-first century, hairdressers cut, color, and style the hair, and have to keep up with the latest trends in order to keep their customers happy and looking fashionable. The same holds true for late eighteenth century hairdressers in England and France. They were dressing their costumers with an elaborate style known as the pouf. It was made of the woman’s real hair and various accoutrements, which could include such things as false hair, powder and pomade. The hair was also decorated with such adornments as flowers, ribbons, pearls, and feathers.

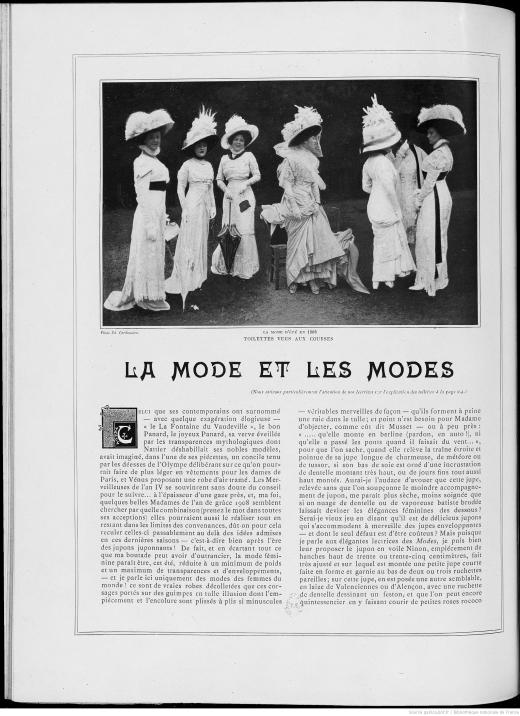

Seeing fashion plates of poufs, and reading first- hand accounts of them, I begin to think that these late eighteenth century hair styles are probably the most extravagant, if not elaborate, hairstyles in the history of fashion. They represent an idea of fashion being non-sensible. Fashion plates from the Galerie des Modes from the years 1778-1787 offer a wonderful source for the fashionable styles of the pouf in its own time period.

The poufs of the 1770s and early 1780s are characterized by extreme height and many decorations, often the adornments on top of the hair are as high as the hair itself. Many styles were named and presented in fashion plates. One style that captures the attention was called La Belle Poule worn in 1778 in honor of the French war ship of the same name that won a naval battle that year and included a miniature version of the ship perched on the hair. Other popular styles included the pouf aux sentiments that could show personal interests or events of the wearer, or the pouf a la circonstance which were inspired by crazes, like ballooning or other events such as plays, war victories and even the storming of the Bastille. Rose Bertin (marchandes des modes to Marie-Antoinette) created many pouf a la circonstance, which not only showed off her craft and talent, but also how she was able to catch when fashions would change. Other styles included adornments of vegetables, flowers, ribbons, jewels, and feathers.

To hold all these excessive and cumbersome decorations, the hair had to be very high and very carefully put together. In order to achieve this style, the hair was piled over of some sort of padding of wool, cotton, false hair, or horsehair. The hair was then powdered, and pomade was applied. The hair, along with the pouf ornamented with such things as feathers and flowers, must have made even walking cumbersome for the lady wearing it.

In her memoirs Madame de la Tour du Pin, lady in waiting for Marie Antoinette, writes of wearing the pouf:

fashions of that day made dancing a form of torture…hair dressed at least a foot high, sprinkled with a pound of powder and pommade which the slightest movement shook down on the shoulders, and crowned by a bonnet known as a ‘pouf’ on which feathers, flowers and diamonds were piled pell-mell – an erection which quite spoiled the pleasure of dancing. A supper party, on the other hand, where people only talked or made music, did not disturb this edifice.The pouf’s heyday was in the 1770’s and maybe the very beginning of the 80’s, in terms of extravagance and constantly changing styles. Hairdressers, such as the famed Leonard, rose to the level of celebrity at this time. The majority of hairdressers were men, including Leonard, who was self-described as “an Academician in Coiffures and Fashion.” He was probably the most famous hairdresser of all time. He coiffed Madame du Barry, succeeded another well-known hairdresser Le Gros, and in 1780, he took over for Larseneur as the “coiffeur-valet” for Marie-Antoinette.

Another well-known figure in the fashion world and in the world of the pouf was not a male or a hairdresser by trade, but a marchande des modes, named Rose Bertin. Mlle. Bertin, mentioned briefly earlier with the creations of the pouf a la circonstance, had clients of nobility, probably the most famous one being Marie-Antoinette. In February 1776, a group of six merchant guilds decided that women of certain guilds (embroiderers, hairdressers, and fashion-makers) could be included into this group of mastership. Rose Bertin was a member of the fashion-makers guild, officially called The Guild of Makers and Dealers in Fashion – Feather-Dealers and Florists of the City and Suburbs of Paris; and was head of the guild for a year from October 1776 to October 1777. The guild choosing Mlle. Bertin as master showed her prominence and success in the trade world in Paris.

Poufs were such extreme styles, and their contemporaries appear to have loved to criticize and satirize them. They certainly were not easy to wear given, not only their enormity, but also all of the accoutrements that went into making one, as shown by the earlier quote from Madame de la Tour du Pin’s memoirs. It is written in the secondary literature that women’s head-dresses and hair were so high at a point that they could not properly fit into their carriages. In his letters Horace Walpole, British art historian and politician of the eighteenth century, has a very stiff opinion about fashion of the 1770s and 1780s. On September 8, 1782 he writes:

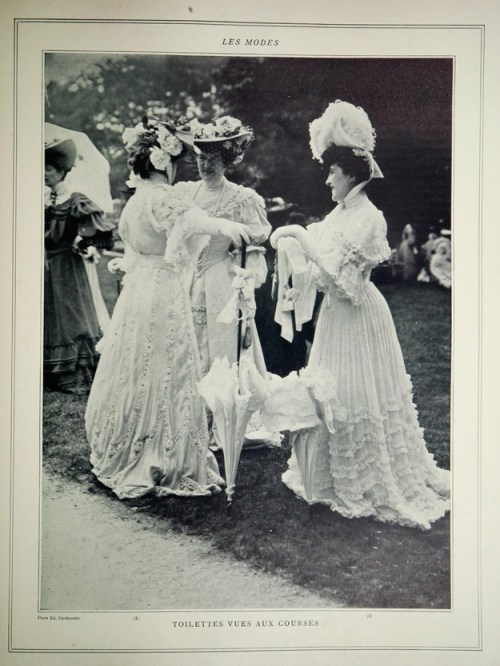

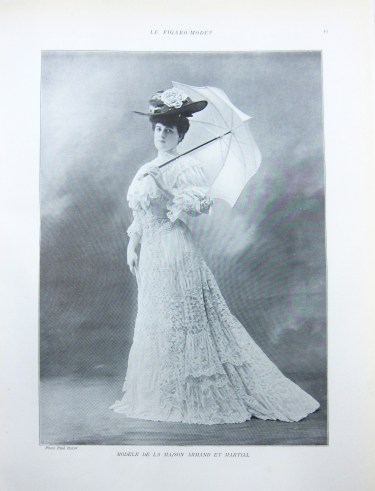

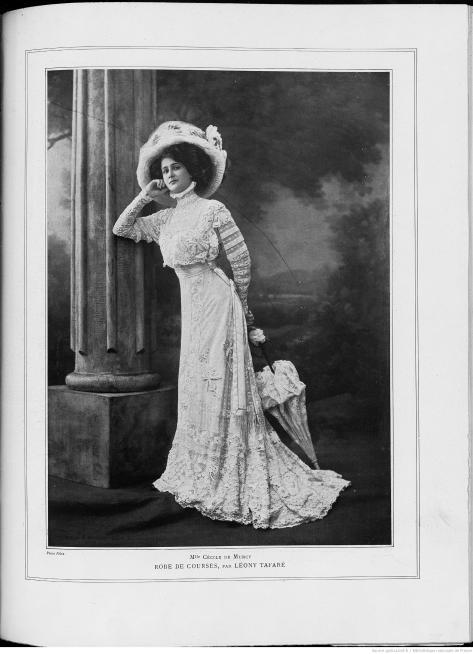

Fashion is always silly, for, before it can spread far, it must be calculated for silly people; as examples of sense, wit, or ingenuity could be imitated only by a fewThe print above was shown at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition of caricatures. It shows only the back view of an elaborately done pouf and the derriere and legs of a woman with stockings, garters, and high heels. This print is a satirical image reminiscent of actual fashion plates such as these seen above from the Galerie des Modes. The caption written by the museum says that this print suggests that the followers of this fashion were brainless.

The French print Le Triomphe de la Coquetterie (below0), also from the same exhibition, shows two women with incredibly elaborate poufs piled enormously high with larger than life feathers, many flowers and pearls. These women are standing on two platforms in the middle of a pool jousting to win an impossibly large and elaborate head-dress in the middle of them. Two other women have already been defeated with one in a rowboat, looking like she has just been pulled from the water with her pouf ruined; and another being pulled from the water bald-headed with her head-dress floating in pieces in the water. The women spectators have unrealistically high and elaborate poufs themselves of all shapes and sizes larger than their person. The inscription, written in French, on the bottom chides the women (the coquettes) for their frivolity in fighting over an item of fashion, and asks them if they would do the same for wisdom and virtue.

Caricatures offer a great source of society’s view of the elaborate pouf outside of the fashionable world. Whether one liked the pouf or not, they were fantastic hair styles with respect to the extravagancies and elaborateness they achieved; the like of which, I suggest, has not been seen in fashion since. The pouf was possibly the most extravagant hair style in fashion, of all time, and I would suggest, continues to fascinate us today.

Selected Bibliography

Cornu, Paul. Galerie des Modes et Costumes Francais: dessinesd’apres nature 1778-1787. Paris: E. Levy,1912.

Corson, Richard. Fashions in Hair: The First Five Thousand Years. London: Peter Owen Ltd., 1965.

Gouvernet, Henriette Lucie Dillon (Madame de la Tour du Pin). Memoirs of Madame de la Tour du Pin. Translated and edited by Felice Harcourt. New York: McCall Publishing Co., 1971).

Langlade, Emile. Rose Bertin: The Creator of Fashion at the Court of Marie Antoinette. Translated by Dr. Angelo S. Rappoport. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913.

Ribiero, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1750 to 1820. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.