After the spring 2010 Christian Dior haute couture show, John Galliano cited a trip to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as the inspiration for his collection. Galliano explained, “I was reading that, actually, it was Charles James who influenced Monsieur Dior to come up with the New Look. And then I was looking at a photo of Charles James doing a fitting…And that was it!” Galliano’s collection brought Dior and James together, referencing their shared history as leading contributors to the history of fashion design. It is not surprising that Galliano connected James and Dior, a relationship that has been a source of interest ever since presentations of both of their collections in Paris in 1947. Exploring the relationship between James and Dior more fully will connect them through friendships, places and clients. Plotting the points of intersection between their careers and lives contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of two of the most influential designers of the twentieth century.

When comparing their design styles it becomes clear that James and Dior shared some stylistic preferences. For example, Christian Dior’s dinner dress “Chérie” from 1947 and Charles James’ dinner suit from 1951 (figure 1 and 2) reveal design similarities, primarily in silhouette. Both designs reflect the fashionable silhouette of the “New Look,” by combining sloping shoulders with a cinched waist and a full skirt, but each designer then used material differently in order to arrive at the desired shape. Dior creates volume in the skirt by using considerable amounts of fabric, whereas James’s use of fabric is more restrained and the skirt retains its shape by means of complex seaming and intricate understructures. James’ design is like a sculpture in the sense that it does not need a body in order to hold its shape. Dior’s dinner dress, on the other hand, sculpts the wearer’s body making the body an anchor by tacking the fabric at the waist. How they chose to work defined the look of their designs, making it relatively easy to differentiate a Charles James from a Christian Dior. While their work is distinctive, James and Dior did not create in a vacuum and were connected as part of the same generation of designers, inevitably tapping into the same influences and reflecting the spirit of the time.

Figure 1: Christian Dior, "Cherie", Dinner Dress, Silk, 1947, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 2: Charles James, Dinner Suit, Silk, 1951, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Putting the issue of design preferences aside, James and Dior viewed each other as colleagues and undoubtedly respected each other as designers and innovators. James wrote enviably of Dior’s position as a designer in Paris, where he was supported financially as well as creatively. James argued that this support, paired with Dior’s talent as a designer, had allowed Dior to create himself in the context of the French couture.[1] James viewed Dior as a fashion leader whose opinions were valued and whose design choices were followed, unlike in America where “fashion leadership…is not in the hands of fashion creators, but in the hands of stylists, fashion coordinators, buyers and salespeople.”[2] Dior held a similarly grim view of the state of the American couture: “couture, in the Parisian sense, scarcely exists in America,” except for the “undoubted talents of Mainbocher, Valentina ,Charlie James, and others…[who] keep [the American couture] in existence.”[3]

In 1929, James had established himself in London as a designer but was frequently traveling between Paris, London and New York. James’s records indicate that in 1934 he established a Paris residence, salon and workshop at the Hotel Lancaster. Concurrently, Dior was in Paris where he had opened a gallery in 1928 along with several artists, including fashion illustrator Christian Bérard. However, the gallery enjoyed only a few years of success, opening as it did just a few years before the Great Depression, and was forced to close its doors in 1934. Jobless and penniless, Dior was forced to look for other work. Encouraged by a friend, Dior began selling fashion sketches to Paris-based designers. Dior’s meticulous records show that between 1935 and 1938 he was sketching for couturiers including Madame Grès, Cristobal Balenciaga and Jean Patou and had accounts with many great milliners of the day including Suzy, Agnès, and Rose Valois. Interestingly, during these years James worked as a milliner and dress designer. Further research would be useful in order to compare Dior’s sketches with Charles James designs, to see if a match could be made.

During the final years of the 1930s, both men were immersed in the world of the Paris couture. On the one hand James had his first showing in Paris in 1937, for which he received much attention and praise, including from an aging Paul Poiret who announced, “I pass you my crown, wear it well.” Dior’s reputation as a talented fashion illustrator garnered him a job, and in June 1938, Dior was hired as a modéliste for the couturier Robert Piguet. Both James and Dior continued designing in Paris until the fall of 1939 when James returned to New York, “with the idea of devoting his talents to the styling of American women,”[4] and Dior was drafted in the French army, leaving the fashion world far behind.

By October 1941, Dior had returned to Paris and began work as a designer (along with Pierre Balmain) at the house of Lucien Lelong, where he was to stay until December 1946. That same year the French textile millionaire Marcel Boussac, proposed to finance a couture house under Dior’s design direction, an offer which Dior accepted. In February 1947 Dior unveiled his inaugural collection, which was christened the “New Look” by the fashion press. Five months later, in July, Charles James returned to Paris to show a selection of day and evening creations. The show was a success and attendees included “distinguished members of international society,” most importantly Dior. The New York Times reported that Dior, Jacques Fath and Elsa Schiaparelli lent James their “loveliest manikins [sic],” while Paulette lent her latest hats. The article describes James’ reputation in Paris as having been established prior to the war and as “a great friend of the French couture.”[5] This article makes explicit that James was respected by the French couture; so well respected that Paris’ top couturiers were willing to lend him their mannequins and designs. Clearly, Dior knew James by reputation and as a designer, but this article supports the idea that they also knew each other personally, and may have been friendly. The following year the columnist “Austine” (Mrs. William Randolph Hearts) wrote in the introductory text to the exhibition “Decade of Design” at the Brooklyn Museum, that Dior had credited James as inspiring the “New Look,”[6] further evidence of their collegiality.

The House of Dior began its foreign expansion in 1948, when it opened a ready-to-wear branch in the United States at 730 Fifth Avenue at Fifty-Seventh Street in New York City. Unfortunately, the new premises had no workspace and consequently Dior was forced to rent a brownstone a few blocks away at Sixty-Second Street. Here he established his workrooms and dressing rooms.[7] Virginia Pope reported the “wholesale” opening for the New York Times, an atypical fashion story, but one that was told “because it is of news importance to have a great Paris couturier, one who has created such a furore [sic] during past seasons, venture in New York competition with our own seasoned and expert designers.”[8] One such seasoned American designer was Charles James.

Charles James had a fragmented business. James was constantly moving his shop, studio and personal residence. However, we know that in 1948 James was located at 699 Madison Avenue, where he had been since early in World War II.[9] The cross street at 699 Madison Avenue is East Sixty-Third Street, a mere two blocks from Dior’s work rooms and six blocks from the Dior salon. Additionally, James was living at the Hotel Delmonico, now the Trump Park Avenue, located at Park Avenue and East Fifty-Ninth Street, just two blocks from the Dior salon. Plotting the addresses on a map of New York makes visible the incredible proximity of the two designers at this time (figure 3).

Figure 3: Map showing business and personal locations of Dior and James, Midtown, New York

Dior came to New York twice a year to work on his American ready-to-wear collections, which were presented in October and in April. These designs were specific to the American market and were designed by Dior in New York as they were “independent of his Paris couture collections…exclusively for American women, keeping in mind her mode of living.”[10] During these month-long trips, Dior designed outside of the French couture for a different, less exclusive, North American market. Dior must have frequented New York social functions, interacting with American designers and society in order to better understand his new market and their “mode of living.” That Dior and James were in such close proximity and were part of the same milieu makes it likely that the two couturiers found themselves at the same social gatherings, a possibility supported by Dior’s own words:

The first discovery I made was that New York – one of the great capitals of the world – is in fact nothing but a village. It is also a village with strict geographical limits…There, and there only, will you find the three hundred people who make up New York. As the problem of going any way by car has become insoluble, you will meet them every day, strolling along the pavement, exactly as one parades along the boulevards in Paris. If you stray far from Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue, you leave the village.[11]

Dior goes on to describe the predictability of living in New York, a city that lulled him into a rhythm where he inevitably saw the same faces in the same places. Perhaps one of those faces was that of Charles James.

James attended Harrow School in Middlesex, England for three terms, where he made several life-long friends, including the photographer Cecil Beaton.[12] In his diaries Beaton describes his fraught, but lasting, friendship with James:

Years passed and in New York we became friends again. His talent was marvelous. His wit bitter! I could not but be his friend. A terrific row fell upon us. We fell apart. The letters he wrote me filled a volume. After a time I became a friend again, and so it went on. I never knew if we were “on” or “off.”[13]

Despite their complicated friendship, James and Beaton were to collaborate often. This early portrait of James, taken by Beaton in 1929 (figure 4), reveals a tenderness between sitter and photographer. As a photographer for Vogue for over half a century, Beaton took countless fashion photographs of couture designs, including this photograph of Charles James gowns for Vogue from 1948 (figure 5). Beaton also photographed Mrs. Charles James in a design by her husband, underscoring their professional, as well as personal, relationship (figure 6).

Figure 4: Cecil Beaton, Portrait of Charles James, 1929

Figure 5: Cecil Beaton, Photograph of Charles James Govns, Vogue, 1948

Figure 6: Cecil Beaton, Mrs. Charles James, 716 Madison Avenue, New York, 1955

Considering Beaton’s prominence in the fashion world it is no surprise that Dior and Beaton also shared a friendship. Dior wrote the preface to the French version of Beaton’s 1954 book The Glass of Fashion, in which Beaton dedicated an entire chapter to Dior and Balenciaga, whom he referred to as the “King Pins” of fashion.[14] As further evidence of their affinity, Dior named a dress from his spring/summer 1951 collection, “Cecil Beaton” (figure 7).

Figure 7: Christion Dior, "Cecil Beaton" Evening Dress, Silk, cotton, Spring/Summer 1951, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Another important figure in the lives of both designers as well as Beaton was Christian Bérard, painter, set and costume designer and fashion illustrator. Dior and Bérard were close friends and it was Bérard, Dior’s “big brother,” who gave the toast at Dior’s celebratory dinner on the eve of his first collection in 1947. In his memoirs, Dior remembers Bérard’s toast: “savor this moment of happiness well, for it is unique in your career. Never again will success come to you so easily: for tomorrow begins the anguish of living up to, and if possible, surpassing yourself.”[15] Bérard was also important to Dior’s work as a designer, often contributing design ideas, sketching his collections and influencing the décor for the Dior boutique at 30 avenue Montaigne.[16] According to Cecil Beaton, after Bérard’s death in 1949, friends worried that “Dior would not be able to exist without him.”[17]

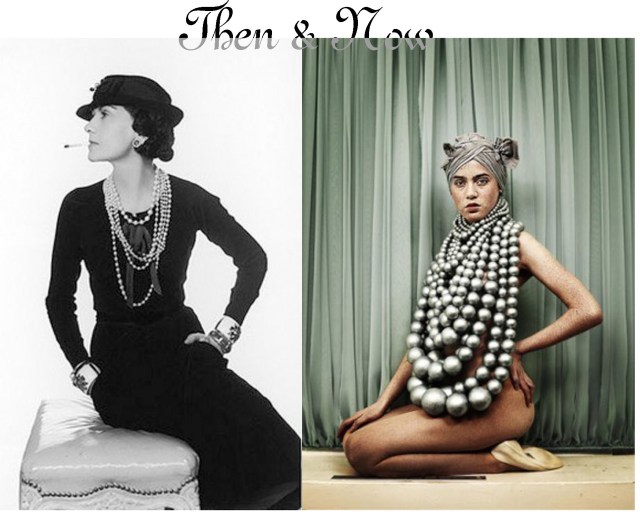

In 1947 James was the first American designer to show in Paris after the war. James’s show at the Hotel Plaza-Athénée was a triumph. James’s “old friends” Christian Bérard and Comte Etienne de Beaumont sent out invitations to the event.[18] This photograph, published in Vogue in 1936, further connects the mutual friends: the designs are by Charles James, photographed by Cecil Beaton and the background painted by “a friend of both the photographer and the designer,”[19] Christian Bérard (figure 8).

Figure 8: Cecil Beaton, Four models wear Charles James Mantles, Vogue, 1936

The Comte Etienne de Beaumont was a prominent society figure and one of the great hosts of the 1920s and 1930s. As was mentioned, the Comte sent out invitations for James’s 1947 Paris showing, but according to another article for The New York Times, James was to exhibit his collection at the Comte’s palace.[20] Further, the Count’s wife, Comtesse Etienne de Beaumont, is found on a list of known Charles James clients.[21] References to the Comte also appear in Dior sources. Much like Bérard, de Beaumont was in the habit of dropping by Dior’s studio on the avenue Montaigne in order to comment on the status of the renovations.[22]

Earlier in his career, in 1934, James lived at the Hotel Lancaster along side his friend Jean Cocteau.[23] More than neighbours, James established a competition at the Paris branch of the Parsons School of Design for the best adaptation of Cocteau’s motifs for printed scarves.[24] Cocteau figures in Dior’s life as well. In his memoirs Dior describes his circle of friends, who were brought together “purely by chance, or rather in obedience to those mysterious laws christened by Goethe with the name of elective affinities…We were just a simple gathering of painters, writers, musicians and designers, under the aegis of Jean Cocteau and Max Jacob.”[25] One wonders if Dior’s gathering of artists ever met at their leader’s residence – an address Cocteau shared with Charles James – at the Hotel Lancaster.

It is important to note the particular relationship that formed between client and designer. The act of buying a couture design was an investment, in both time as well as money. Couture garments were, by definition, not ready “off-the-rack” and consequently clients came to the designer’s studio for multiple fittings before a garment was ready to be worn. The process of producing couture was expensive and, particularly after World War II, accessible only to a few. Consequently, it is useful to consider the dynamic between society women and designers as mirroring that of a patron and artist. James was saved from financial ruin (on more than one occasion) because of the support of a few clients, who were not prepared to witness the demise of an artistic genius. Mrs. William Randolph Hearst, one of James’ most devoted clients, writes of her dedication to James: “we must forgive geniuses their transgressions…influential, responsible leaders at the peak of the fashion pyramid, store owners, editors, commentators – even customers – must dedicate themselves to searching for and developing American’s designing talent.”[26]

In light of these observations, it is telling to note a sampling of the clients that patronized both Charles James and The House of Dior. This shared clientele included, but was not limited to, Marlene Dietrich, Mrs. Byron Foy, Marie-Louise Bousquet and Mrs. Hearst. These women were considered arbiters of style and accordingly, were photographed in James and Dior designs for fashion periodicals and other publications. Having their garments publicized on the backs of stylish society connected the designers as colleagues and artists. This camaraderie is best illustrated through one particular client, Mrs. Hearst, who was referred to Dior by James himself.[27]

The points of intersection between Charles James and Christian Dior are undeniable. They frequented the same social circles and shared close friends and clients. They lived in the same cities – from Paris to New York – mere blocks from one another. They collaborated with the same artists and had their work lauded and featured in the same publications. Beginning in the 1930s, they certainly knew of each other and were probably acquaintances or even friends. However, the exact nature of their relationship and the details of how they may have influenced each other’s work remains unclear. For now, their designs live on in museum collections, their stories continue to be told as part of the narrative of fashion history and their legacies continue to inspire new generations of designers.

Bibliography

Beaton, Cecil. The Glass of Fashion. New York: Doubleday, 1954.

——. The Unexpurgated Beaton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

“Charles James Exhibits Styles in Paris; Society Acclaims U.S. Designer’s Artistry.” The New York Times, July, 1942.

Coleman, Elizabeth. The Genius of Charles James. New York: The Brooklyn Museum, 1982.

Dior, Christian. Dior by Dior: The Autobiography of Christian Dior. London: V & A Publications, 2007.

“Mainbocher Back, Winces at Corset.” The New York Times, October, 1939

Palmer, Alexandra. Dior: A New Look, A New Enterprise. London: V & A Publishing, 2009.

Park, Eun Kyung. “From Couture to Ready-to-Wear: The 1950s Designs of Charles James.” Master’s Thesis, Fashion Institute of Technology, 1994.

Pochna, Marie-France. Christian Dior: The Biography. New York: Overlook Duckworth, 1996.

Pope, Virginia. “Designer Taking Creations to Paris.” The New York Times, July, 1947.

—–. “Dior, At Opening, Copies Himself.” The New York Times, November, 1948.

—–. “Styles of Decade in Museum Exhibit.” The New York Times, November, 1948.

Endnotes

[1] Charles James, “Fashion Foibles,”

Dioplomat (May 1955): 59.

[2] Charles James, “Fashion Foibles,” 59.

[3] Christian Dior, Dior by Dior: The Autobiography of Chrsstian Dior, (London: V&A Publications, 2007): 30.

[4] “Mainbocher Back, Winces at Corset,” The New York Times (Oct, 1939): 22.

[5] “Charles James Exhibits Styles in Paris; Society Acclaims U.S. Designer’s Artistry,” The New York Times (July, 1942): 16.

[6] Elizabeth Coleman, The Genius of Charles James (New York: The Brooklyn Museum, 1982): 84.

[7] Marie-France Pochna, Christian Dior: The Biography (New York: Overlook Duckworth, 1996), 192.

[8] Virginia Pope, “Dior, At Opening, Copies Himself,” The New York Times (Nov, 1948): 32.

[9] Virginia Pop, “Styles of Decade in Museum Exhibit.” The New York Tmes (Nov, 1948): 34.

[10] “Christian Dior Will Design Clothes Here; Wholesale Salon to be Opened in October,” The New York Times (Aug, 1948): 18.

[11] Dior, 49.

[12] Coleman, 78.

[13] Cecil Beaton, The Unexpurgated Beaton (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), 478.

[14] Pochna, 262.

[15] Dior, 32.

[16] Dior, 149.

[17] Cecil Beaton, The Glass of Fashion (New York: Doubleday, 1954), 263.

[18] Coleman, 84.

[19] Coleman, 16.

[20] Virginia Pope, “Designer Taking Creations to Paris,” The New York Times (July 1947): 28.

[21] Coleman, 173.

[22] Pochna, 120.

[23] Coleman, 81.

[24] Coleman, 81.

[25] Dior, 176.

[26] Mrs. William Randolph Hearst in Elizabeth Coleman, 115.

[27] Pochna, 168.