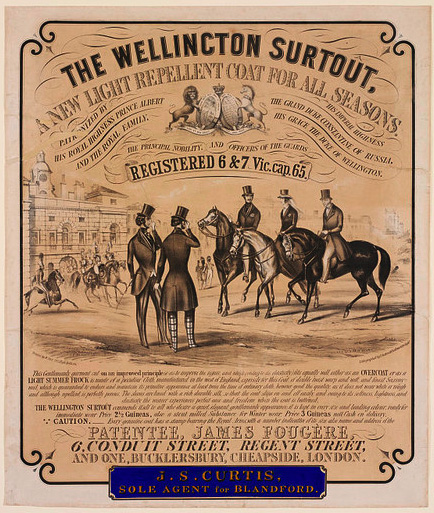

A woman is fitted in a woefully out-of-style crinoline. “The Anti-Suffrage Society as Dressmaker,” Suffrage Atelier, ca. 1909-1912, Museum of London.

Although this image is from the English women’s suffrage movement, the message still pertains to its American counterpart: as unbecoming as an old fashion is, so are asinine outdated social rules. Just as fashion progresses, so does society, and in the nineteenth century the women’s suffrage movement worked towards advancement.

In the United States, 1920 was the first year when millions of women exercised their right to vote. The women’s suffrage movement had had its seeds planted nearly one hundred years earlier, prior to the advent of the Civil War. It is impossible to say that woman’s suffrage had a style of its own, but Fashion has a way of permeating social movements, feminist women’s rights endeavors included.

Within the timeframe between the 1850s and 1920, women’s fashion went through many changes: bulky petticoats gave way to the cage crinoline; skirt shapes shifted from voluminous circles to grand ellipses; the bustle grew, then contracted, then returned, then slimmed for good; sleeves puffed higher and wider; backs were swayed; skirts were hobbled; a tiny bit of ankle dared to show itself. Fashion went through its own motions, and a woman could not be labeled as pro- or anti-suffrage simply based on her clothing.

Many women’s rights activists were quite anti-fashion. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of the most influential women’s rights reformers, claimed that fashionable dress was an acceptance of female oppression. Sojourner Truth, a freed slave who joined the women’s rights movement, remarked “What kind of reformers be you, with goose-wings on your heads, as if you were going to fly, and dressed in such ridiculous fashion, talking about reform and women’s rights? ‘Pears to me, you had better reform yourselves first.”

Perhaps one of the most well-known quirks in women’s fashion in the nineteenth century is due to Amelia Bloomer, a women’s rights activist, who boldly began wearing wide, billowing trousers gathered at the ankle with a short, full skirt over them. The look was ridiculed in the press. Whether it was viewed as immoral, ugly, or in conflict with the view of what a woman’s place in society should be, it was not widely copied and did not catch on to the mainstream.

Woman in Bloomer costume, 1851, Library of Congress.

The women’s suffrage movement was derailed by the Civil War, which shifted focus to other areas of social reform. By the 1890s, the United States ushered in the Progressive Era, and the concept of the New Woman was introduced—a woman who worked in an office, sought higher education, and participated in active sports—and women’s fashions reflected their changing place in society. Daywear lost its frills and furbelows and became more tailored, similar to menswear. University students favored skirts with a shirtwaist. And the sports craze of the 1890s gave way to the acceptance of calisthenics-appropriate attire for women who golfed, played hockey and tennis, and bicycled in public. Trousers and knickerbockers were accepted as appropriate wear for women while engaging in sports.

“New Woman” Fancy Dress Costume, Fancy Dresses Described, 1896.

Cycling costume, American, c. 1895, Kyoto Costume Institute.

By the 1910s, women were granted limited voting rights in a few Western states. Across the Atlantic, Paul Poiret was making advances in fashion that had not been seen—namely in the form of long, corset-less silhouettes and hobble skirts with hems so tight they impeded the gait. “I freed the bust and shackled the legs,” he is said to have boasted.

Poiret’s designs may have prevented women from taking great strides, but not their ability to march. Women by the thousands gathered at parades to demonstrate for women’s suffrage, the largest being in New York City in 1913, when 30,000 gathered to march up Fifth Avenue. According to this New York Times headline of April 25, 1913, what they were wearing was clearly of great concern.

World War I served as the final push to pass the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ensuring that women in all fifty states had the right to vote.

Photograph of Alice Paul standing over ratification banner hanging from the balcony of the National Woman’s Party headquarters, with members watching outside the building below. August 18, 1920. Library of Congress.

In the United States, next Tuesday is Election Day, and however you choose to cast your ballot, take a moment to remember the women who fought long and hard for that right. Just make sure your fashionable sleeves fit into the booth!

“A Squelcher for Woman Suffrage. How Can She Vote, When the Fashions Are So Wide, and the Voting Booths Are So Narrow?” Anti-suffrage cartoon, Puck, 1896, Library of Congress.

Resources

Butler, Mary G. “The Words of Truth: Sojourner Truth Speeches and Commentary.” Sojourner Truth Institute. http://www.sojournertruth.org/Library/Speeches/Default.htm (accessed November 1, 2012).

Cunningham, Patricia A. Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850-1920: Politics, Health, and Art. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2003.

“Fashioning the New Woman: 1890-1925.” DAR Museum. http://www.dar.org/museum/musnews.cfm (accessed November 1, 2012).

Finnegan, Mary Margaret. Selling Suffrage: Consumer Culture & Votes for Women. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Holt, Ardern. Fancy Dresses Described, or What to Wear at Fancy Balls. 6th ed. London: Debenham and Freebody, 1896.

Poiret, Paul. King of Fashion: The Autobiography of Paul Poiret. 1931. London: V&A Publishing, 2009.

Who is this elegant woman? What was her profession?

Who is this elegant woman? What was her profession?