Last week we shared with you Landis Lee’s research on Edward Linley Sambourne, who may have been the original street fashion photographer. This week, on the same topic, here is another fascinating post by one of our students.

By Kathryn Squitieri

While most people think of “street” fashion photography as a phenomenon of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries, in reality, the practice began in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the same time that fashion photography in general was beginning to be used to spread fashion news in the media. Periodicals during this time, particularly French ones like Les Modes and Femina, started featuring photos of fashionable women at society events, such as horseraces and garden parties, as a supplement to their stiff studio photographs of models or actresses posed in the latest couture designs. A few years later, around 1905, American magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar began publishing photos of “real” fashion as well, mostly taken at the French races at Longchamp, Auteuil and Chantilly.

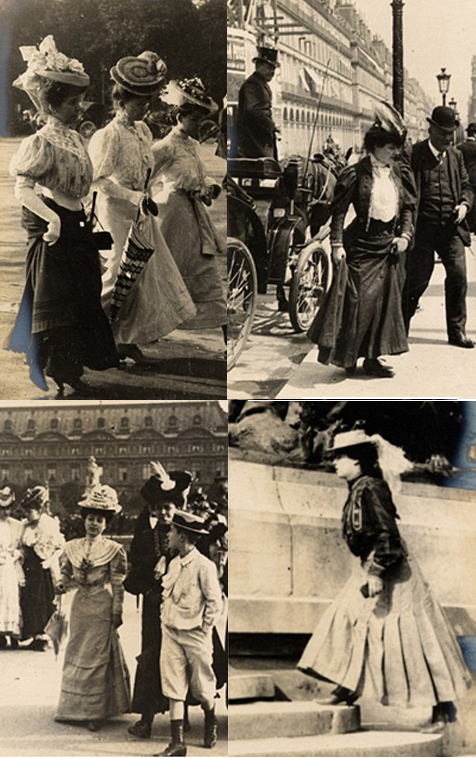

Unknown Photographer, Toilettes á Auteuil, June 19, 1911, Image Collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The various events throughout the racing season were considered the most important places to witness fashionable society women wearing the latest couture gowns. In fact, couturiers often sent their models wearing new designs to mingle with the fashionable crowd and hopefully attract new clientele. The models can usually be recognized by their slim, elegant figures, their youth, and their characteristic poses in photographs, while the “real” women often have figure flaws and may look unsure of themselves if they know they are being photographed.[1] Besides the professional models who were paid by the day, there were other women known as “fashionables” who modeled the clothes. These were well-known society personalities who received deep discounts on their purchases from couture houses if they wore the latest models to important society events, such as horse races.[2]

The racecourses in Paris opened their season in mid-February and closed in mid-July. The most important event, as far as fashion was concerned, took place at the end of June with Grand Prix Sunday at the racecourse Longchamp.[3] That day was “when new fashion trends were established, when couturiers and fashionables observed a pause and agreed on what would be worn the coming year,”[4] writes Xavier Demange. A contemporary source also states the importance of Longchamp:

The day par excellence, the day of days, to every pretty woman, of every class, was that known as Longchamp…the day of Fashion’s great review, when all her battalions were marshaled in array. It was the pet festival of the most elegant section of society, male and female, of all lovers of novelty, and of every idler in Paris. The smart folk went to Longchamp to show off their fine clothes and carriages and prancing horses; the rest went to….speak ill of their neighbours, a practice which has always been in fashion…Longchamp was the great fancy fair, whither every fair Parisian took herself, to draw inspiration for her new gowns, and dream of their perfections.[5]

Being arguably the most important day of Paris fashion of the year, fashion magazines all over the world were required to cover it in order to give women the news of Parisian taste. The periodical Les Modes dedicated their July and August issues from 1903 until the First World War to summer fashions seen at the races. These photos were mostly taken by an obscure photographer known as Edmond Cordonnier, who seems to have specialized in outdoor photography, and who Xavier Demange credits as the first person to take trackside fashion photographs in 1901 or 1902.[6] These unposed photographs were even used for covers at a time when magazine covers featured illustrations.

Edmond Cordonnier, Toilettes Vues Aux Courses, 1904, Les Modes, July 1904.

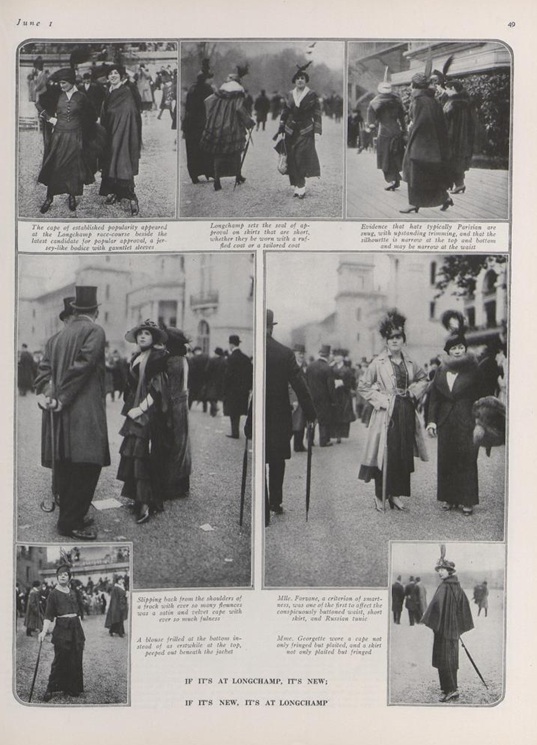

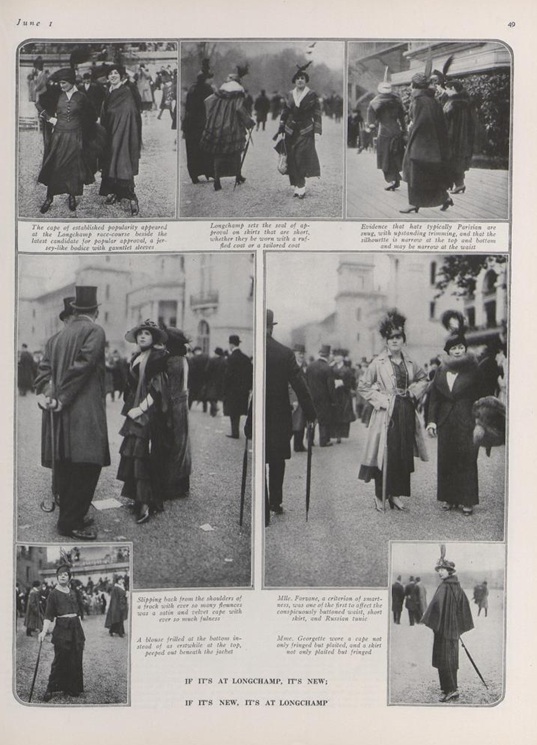

Vogue also covered fashion at the Paris races, mostly using illustrations of the latest modes seen at the racetrack combined with descriptions of the garments. The periodical does not appear to have used photographs for these stories until after 1908. The editorials proclaimed that not only were the fashions seen at Longchamp the culmination of what was fashionable that summer, but hinted at what was to be fashionable that Autumn. A fashion editorial in the June 1, 1914 issue of Vogue proclaimed “If it’s at Longchamp, it’s new; If it’s new, it’s at Longchamp”

“Fashion: Seen at Longchamp,” Vogue, June 1, 1914, 49.

Besides the pioneering Edmond Cordonnier, the Séeberger brothers took fashion photographs of women attending the French races beginning in 1909. The brothers Jules, Henri and Louis Séeberger dedicated themselves to recording society events where the latest haute couture garments were worn. They expanded beyond the racetrack, capturing fashion at holiday resorts and beachside towns where the fashionable would travel to once racing season was over. Their first business stationary read “High-Fashion Snapshots: Photographic Accounts of Parisian Style.”[7] Unlike Cordonnier, who seems to have only worked for Les Modes, the Séeberger brothers sold their photographs to many periodicals, including several published outside of France which included Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Good Housekeeping and the Ladies Home Journal, although most are featured after 1917.

Fashion stories that featured photos of “real” society women and their clothes proved quite successful in Europe and America. Perhaps this is because women were interested in seeing not just what couture houses were imposing on the upper class, but what they were actually wearing. Outdoor photographs also provided the perfect background for the fashionable lingerie dresses that were worn at the turn of the twentieth century. The green grass offset the trains of the white gowns, and wind gave the gowns movement, bringing the fashions to life and likely making them even more desirable. The reader of the fashion magazine also had the chance to see how the dress was accessorized by the woman wearing it. Not only did they see the latest gowns, but they were shown the correct shoes, gloves, parasol, hat, belt, and even stockings that most complimented the dress.

While candid photos of fashionable women were published in fashion magazines, there are many existing examples that were taken by hobbyists or art photographers that were interested in fashion, women, or society in general but did not necessarily consider themselves fashion photographers. Jacques Henri Lartigue, Paul Martin, and Edward Linley Sambourne are three photographers who fit this description. Their photographs tell us a lot about fashion and what women were really wearing around the turn of the twentieth century, but their photographs were not seen in contemporary fashion magazines.

Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986) was born in Courbevoie, near Paris, France to a wealthy family. His father bought him his own camera when he was only seven years old, and he began to take photographs, mostly of his family and his daily life.[8] In his teenage years, however, he became interested in women and began to photograph them out on the street as they walked by. He wrote in his diary, “Women…everything about them fascinates me—their dresses, their scent, the way they walk, the makeup on their faces, their hands full of rings and, above all, their hats.”[9] He described his process of capturing fashionable women: “The [Avenue des] Acacias has three lanes… [including] one for pedestrians. People call this third lane the ‘Path of Virtue.’ And that’s where I am…with my camera….ready for action the moment I see someone really elegant coming along. She: the well-dressed, fashionable, eccentric, elegant, ridiculous or beautiful woman I’m waiting for. ”[10] Lartigue also attended the racetrack in search of fashionable women to photograph . He wrote of one experience: “It is the afternoon of the Grand Prix horse races at Longchamp…Here, nobody seems to mind my taking photographs; on the contrary, the ladies sometimes stand still and pose for me. There are lots of elegant umbrellas around and, as always, amusing dresses…and enormous, beautiful, ridiculous hats.”[11] This quotation suggests that the stylish women at the racetrack were used to being photographed, and even desired to be captured on film, which even further reinforces how important it was for society women to look elegant and be seen at Longchamp and other horseraces. Throughout the nineteen-teens, Lartigue photographed fashionable Paris women out and about on the streets and at the racetrack, capturing the much-desired look of the French elite. However, his photographs have rarely been studied as a source of fashion, and he himself considered his work to be art photography rather than fashion photography.

Jacques Henri Lartigue, Along the Bois de Boulogne, Early 1910s, Reproduced in Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Diary of a Century. New York: Viking Press, 1970.

Jacques Henri Lartigue, At the Auteuil Races, 1912, Reproduced in Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Diary of a Century. New York: Viking Press, 1970.

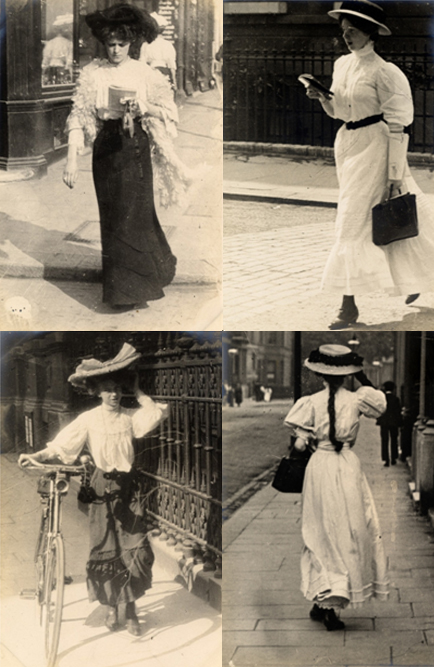

Paul Martin was born on April 16, 1864 in Herbeuville, France, but made his life in London, England after his parents moved the family there to escape the hardships of the Franco-Prussian War. He worked as a woodcut illustrator, taking up photography as a hobby to aid in his creation of engravings.[12] He began photographing people secretly in 1892, when he purchased a camera known as Fallowfield’s Facile Hand Camera. Advertisements of the camera explained how it could be disguised in a wrapping of brown paper, making it look like a parcel, possibly containing a book or two, wrapped by a shopkeeper.[13] Without the hindrance of a tripod, and with the camera’s ability to take twelve shots before it needed to be refilled with plates, Martin was able to take his street photographs with extreme discretion. The neighborhood he lived in was poor and run down, so most of his photographs are of working class people. However, he did take his Facile camera on holiday trips to Boulogne, Paris and Yarmouth, where he captured fashionable fellow vacationers on film. The result is an incredibly relaxed, natural look that shows us with the least amount of artifice how clothes were being worn during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His photographs of women on the beach or the boardwalk, are particularly telling of casual attire and sportswear.

Paul Martin, Girls in Cycling Bloomers on the Quay in Boulogne, 1897, Reproduced in Roy Flukinger et al. Paul Martin: Victorian Photographer. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1977.

Street-style photography from the turn of the twentieth century tells a truer story about how clothes were worn than can be discovered by looking at studio portraits from the same period. Fashion was captured by artists and hobby photographers, as well as professionals like Edmond Cordonnier or the Seéberger brothers who were paid to capture society women dressed in the newest and most exciting styles for fashion magazines. The most telling photographs, however, are the ones that were taken secretively on the streets, without the subjects knowing they were being photographed, making them look relaxed, more casual, and as a result, not unlike women photographed by Bill Cunningham today.

[1] Xavier Demange. “Trend Setters at the Racetrack,” in Elegance: the Séeberger brothers and the birth of fashion photography, 1909-1939. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2007, 33.

[3] Ibid, 31.

[4] Demange, 31.

[5] Octave Uzanne, Mary Loyd, and François Courboin. Fashion in Paris: The Various Phases of Feminine Taste and Aesthetics from 1797 to 1897. (London: W. Heinemann, 1898), 100-102.

[6] Demange, 31.

[7] Sylvie Aubenas. “The Séebergers, Fashion Photographers: Rediscovering their Place,” in Elegance: the Séeberger brothers and the birth of fashion photography, 1909-1939. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2007, 11.

[8] John Szarkowski and Jacques Henri Lartigue. The Photographs of Jacques Henri Lartigue. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1963, 1.

[9] Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Diary of a Century. New York: Viking Press, 1970, book is not paginated.

[12] Roy Flukinger, Larry J. Schaaf, and Standish Meacham. Paul Martin: Victorian Photographer. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1977, 8-11.

[13] Ibid, 24.