Prevost, Jean. “Modes d’Amerique” July 6, 1931. Found in Fashion Is Spinach by Elizabeth Hawes.

That’s right; this article is about Elizabeth Hawes (1903 – 1971), the fashion designer and author.

Lawrence, Mary Morris. Hawes with Models, c1936. Copyright Mary Morris Lawrence. Found in Radical by Design.

TO

MADELEINE VIONNET

the great creator of style in France

AND TO

THE FUTURE DESIGNERS OF

MASS-PRODUCED CLOTHES

the world over

…So begins Fashion Is Spinach, Elizabeth Hawes’s first book, in which she describes her career:

“I, Elizabeth Hawes, have sold, stolen, and designed clothes in Paris. I have reported on Paris fashions for newspapers and magazines and department stores. I’ve worked with American buyers in Europe.

“In America, I have built up my ivory tower on Sixty-seventh Street in New York. There I enjoy the privilege of making beautiful and expensive clothes to order for those who can afford my wares. I ran the show myself from the business angle for its first four years. I have designed, sold, and publicized my own clothes for nine years.

Hawes, Elizabeth. “The Moonstone.” Rust chiffon, chartreuse, and blue satin evening ensemble, Spring/Summer 1938. Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“At the same time, in New York, I designed one year for a cheap wholesale dress house. I’ve designed bags, gloves, sweaters, hats, furs, and fabrics for manufacturers. I’ve worked on promotions for those articles with advertising agencies and department stores….

“During the course of all this, I’ve become convinced that ninety-five percent of the business of fashion is a useless waste of time and energy as far as the public is concerned. It serves only to ball up the ready-made customers and make their lives miserable” (11).

Hawes, Elizabeth. “Jolanthe” Greek-inspired sheath, Fall/Winter 1932. Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hawes received her education at Vassar before moving to France in 1925. With the help of a friend, she found her first job working at Doret’s, a copy house, where she sold dresses and sketches to American buyers.

“A copy house is a small dressmaking establishment where one buys copies of the dresses put out by the important retail designers. The exactitude of the copy varies with the price, which varies with the amount of perfection any given copy house sees fit to attain…. Most copy houses in Paris are upstairs, on side streets, although the one in which I worked was on Faubourg St., Honoré, just a bit up from Lanvin near the Place Beauvais. It was a very good copy house. Our boast was that we never made a copy of any dress of which we hadn’t had the original actually in our hands” (Fashion is Spinach, 38).

Hawes found her work at the copy house to be less than satisfying and found new work as a fashion journalist and a buyer. Still hoping to learn more about dress design, Hawes began working for Madame Nicole Groult, a small fashion house, in April 1928. While working with Madame Groult, Hawes learned the design process, from buying fabric to showing the finished models. Hawes worked with Madame Grout until August; after determining that she had mastered the design process, Hawes returned to New York City.

In New York City, Hawes opened a small shop with a young socialite, Rosemary Harden. Together Hawes-Harden produced its first collection in 1928, and contained some gems like the long-skirted, high-waisted dress which Hawes entitled “1929, perhaps–1930, surely”. Many of Hawes’s witty ensembles have equally clever or interesting names, including the garments described in the article above.

Hawes, Elizabeth. “Diamond Horseshoe” evening dress, Fall/Winter 1936-1937. Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hawes, Elizabeth. “Diamond Horseshoe” evening dress, Fall/Winter 1936-1937. Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hawes’s uniquely American style was totally removed from French fashion trends, with the exception of her fabric choices. Though she purchased French fabrics, Hawes ignored the latest collections from established French fashion houses, choosing instead to design for the American woman. She created elegant ensembles for the American lifestyle, with each design stemming from her advanced knowledge of construction techniques and her complete knowledge of fabric properties. Rather than relying on embellishment, Hawes created visual interest by her use of lines, color, and fit.

When Harden left the clothing business, Hawes began a successful solo career, designing clothes through the depression years under the label Hawes Incorporated. In Fashion is Spinach, Hawes describes the difficulties she faced during the depression, and how she began to discover the benefit of mass-producing ready-to-wear clothing. Unlike her contemporaries, Hawes foresaw the importance of ready-to-wear design, and as an early proponent, she worked closely with department stores like Lord and Taylor.

There is much to say about Elizabeth Hawes, and fortunately, she authored a series of books filled with her opinions on fashion, women’s rights, unions and more.

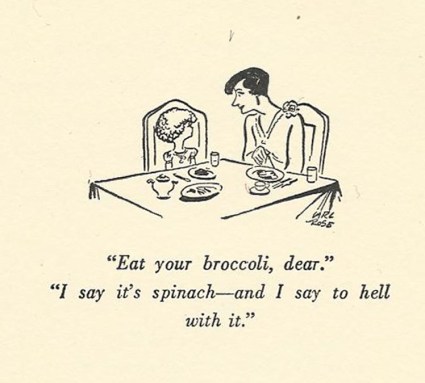

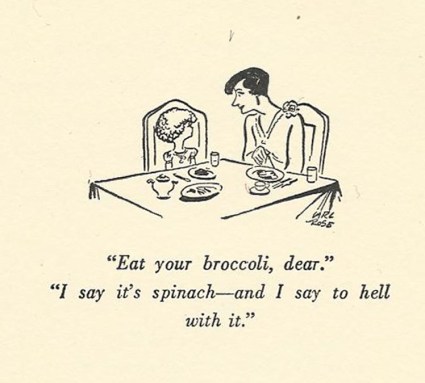

So, why is fashion spinach?

“I had better, right here, differentiate for your between Fashion and Style, according to Webster, Hawes, and Shakespeare. Mr. Webster says Fashion is dressing in a way which is favored at the time, while Style implies a distinctive manner of dressing adapted by those who have taste. In Fashion Is Spinach, I defined Fashion as a dictator who not only forced people to dress in the way he favored at the time but also did his best to force perverse changes in women’s clothes as rapidly as possible so that American business could sell more things. Fashion, said Shakespeare, is a ‘deformed thief'” (It’s Still Spinach, 60).

From Fashion Is Spinach.

For more information please see the following resources:

Birch, Bettina. Radical By Design: The Life and Style of Elizabeth Hawes. New York: Dutton, 1988.

Hawes, Elizabeth. Fashion Is Spinach. New York: Random House, 1938.

Hawes, Elizabeth, Men Can Take It. New York: Random House, 1939.

Hawes, Elizabeth. Why Is A Dress? New York: Viking Press, 1942.

Hawes, Elizabeth. Why Women Cry; Or Wenches With Wrenches. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, Inc., 1943.

Hawes, Elizabeth. Hurry Up Please It’s Time. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, Inc., circa 1946.

Hawes, Elizabeth. Anything But Love. New York: Rinehart & Company, Inc., 1948.

Hawes, Elizabeth. But Say It Politely. Boston: Little, Brown, 1951.

Hawes, Elizabeth. It’s Still Spinach. Boston: Little, Brown, 1954.